Ever since I started plant-dyeing a lot, I have thought of travel as more than a chance to see my friends in other places or to sit in a sardine tin of a seat eating airplane food: it has become a chance to see what plants are growing wild in other environments and to collect what my friends don’t need in their gardens that might be productive dye plants. It’s dyeing tourism. I went to England a couple of weeks ago to visit my knitting friends there for a long weekend in a big weekend rental house in Henley-on-Arden, Warwickshire, near Stratford-on-Avon, where I planned to spend the time in an orgy of plant dyeing with a knitter named Liz, who unlike me, has learned about natural dyeing from people who know what they’re doing.

My husband and I arrived in England a day early and visited my friend Rachel and her husband Mark at their house in Fladbury, which is a couple of towns away from the weekend house. Rachel is the one who made machine knitting seem interesting enough for me to overcome my misgivings about scary complicated machines with a million ways to cause disasters. It was wonderful to see them; the husbands were compatible, Rachel and I had a lot to talk about, and our hosts took the kindest and most solicitous interest in showing us their lovely countryside and feeding us just-picked seasonal vegetables. I showed Rachel my machine-knit ponchos and she showed me beautiful stitches and embellishments she had invented on her knitting machines, and she took me on a walk to their allotment, where she gave me calendula blossoms and rhubarb stalks and leaves for the weekend’s dyeing experiments. While we were in her garden visiting her chickens, she reached down and yanked out an invasive weed called ground elder, which she gave to me in hopes that it might be good for something and yield some color. Every moment in their presence was a pleasure, and we were sorry to say goodbye when they dropped us off at the weekend house.

But we were at the weekend house, and there was Liz with all her dyeing equipment! We hadn’t met in person before, but from the moment we met, it was as if we had been friends for years. The house had its flaws, such as an infestation of wool-eating bugs, never good news for a group of knitters, but the set-up of the kitchen was perfect for our dyeing purposes because two of the three stoves and the sinks were in an annex of the main kitchen area and everything we needed was within arm’s reach. I had brought six 2-ounce hanks of undyed, superwash lace-weight Wollmeise yarn that I had previously mordanted in alum and cream of tartar, and Liz had loaded her car with unbleached linen, white cotton, and undyed wool for herself and for the other knitters. She had previously mordanted the plant fibers in soy milk to provide them with protein cells onto which the dye could attach. We threw all the yarn into a collapsible plastic tub that Liz had brought with her and soaked it in water, then dumped Rachel’s calendula blossoms into a pot and started boiling them. It gave a little bit of yell0w-green color. We also boiled the ground elder and it yielded no color at all, so we pitched it. We put two of my 2-ounce Wollmeise lace hanks and a hank of linen into that bath and left them overnight. In the morning, the Wollmeise hanks were a weak dingy yellow and the linen hank was entirely unaffected. Prior to the meet-up, Liz had prepared an avocado stone dye using just over 600g of avocado stones, which she had simmered for 90 minutes, let them cool, then simmered for another hour, before cooling and straining through muslin. The first evening of the meet-up, she put cotton and undyed linen hanks into the prepared avocado bath, heated it, let it cool, and left the yarn in the bath overnight.

The following morning, Liz brewed a hibiscus dye bath, which makes pinks and purples. She put the contents of two boxes of hibiscus tea (90 grams) into a pot for boiling, and as soon as the hibiscus made contact with the cold water, it started releasing intense magenta color even before the water began to heat. After an hour of simmering, the bath was opaque with color. A hank of white cotton turned a shade of floral pink that almost brought tears to my eyes because it was so beautiful and so elusive in my dyeing experience. I dipped a yellowish calendula hank into the hot hibiscus dye for a moment, thinking it might turn orange, and got a pink-brown-gray variegated with dusty rose. It was a lovely mixture, and I took it out of the dye right away because I was happy with it exactly as it was. I left the other calendula hank in the dye for longer, and it became a solid pink-brown-gray. Liz also dyed several hanks of unbleached linen, whose color was a natural brown, and they turned a brown-purple after a day and a half in the hibiscus bath.

Liz reheated the avocado bath where the cotton and linen hanks had been soaking. I had a hank that had turned a yellow tinge after an unsuccessful experiment with fig tree trimmings, so I put it into the hot bath, swirled it around for less than a minute, and it turned the clear apricot orange that I’d read about and had never gotten in my previous avocado experiments. I was overjoyed. Liz floated the theory that brighter orange colors might come from the second exhaust bath of avocado dyes due to oxidation, but we have not tested the theory in any systematic way. The superwash wool took this dye the best. Linen didn’t seem all that receptive to the avocado.

Then it was Rachel’s rhubarb leaves’ turn. We had over a pound of them, which we tore into small pieces with hands protected by rubber gloves, because they are toxic. When we boiled them, the leaves produced little color, and we might have thrown away the bath as we did with the ground elder, had it not been for reference books that showed samples of wool yarn that had been dyed in boiled rhubarb leaves and treated with various pH modifiers and mordants. We divided our bath in two, one treated with alum, an acidic modifier, and the other treated with washing soda, an alkaline modifier. This is where we started getting really witchy. We brought the alkaline bath to a pH of approximately 9.5, based on the color of the litmus strips Liz provided, which colored the cotton and wool a nice strong yellow. The alum bath had a pH of 4, and there was little color after adding a tablespoon and a half of alum and then another tablespoon and a half. Then we poured in a tablespoon or two of white vinegar, and still nothing. Then we decided to see what would happen if we went in the opposite direction, toward alkaline, so we put in about a tablespoon and a half of powdered chalk, and POOF! The brew suddenly puffed up into a yellow meringue froth, almost like an explosion except there was no bang or flying shrapnel, but sudden and shocking nonetheless.

One of the people on my Ravelry group explained what was happening chemically: “Clay (which is typically calcium carbonate or a derivative) + vinegar = a decomposition reaction.

“Historical reference, Hannibal, the Carthaginian general, used vinegar to break a path through the Alps, which are composed of a lot of limestone and clay. What they did was heat the vinegar and then throw it on the mountains to decompose the rocks and make them crumble, crack and break. They fully succeeded in getting through to part of what was then the Roman Empire that way, though Hannibal never succeeded in destroying the empire.”

So if Hannibal could science his way through the Alps with this chemical reaction, surely it could produce an interesting color in our dye vat! I took a few inches of yarn from my solid pink-gray-brown calendula/hibiscus hank and dipped an end into the brew. It instantaneously turned green. Splash, in went the entire hank. Five minutes later my wool skein was an intense woodsy green. The linen hanks stayed in the bath overnight for a celadon green.

Outside the house there was a patch of dock and stinging nettle, plants that can produce yellows, greens, and browns, depending on mordants and modifiers. I was unfamiliar with these plants, although they grow in North America. I was told that stinging nettle really does sting, but fortunately it grows in close proximity to dock, and dock is an antidote to nettle stings. I went out to the patch of dock and nettle, and it was clear which plant was the dock, but I got a little confused about the nettle because it looks soft and furry and not sharp and prickly as I would have expected, and there were sharp and prickly plants in the patch as well. I decided to sacrifice my body to science in order to find out which plant was which, and I found out in a hurry which plant was the stinging nettle and the degree of efficacy dock has in counteracting nettle stings. My friends were very amused by this particular scientific inquiry. I put the gloves back on and resumed cutting the plants, and came back to our dye laboratory with about 360 grams of each plant. We chopped up the leaves and boiled each plant in a separate pot for an hour, and left them to cool.

In the morning, we strained the dock leaves from the bath and put in a superwash Wollmeise Pure hank, a superwash Wollmeise lace hank, a cotton hank, a linen hank, and a hank of non-superwash wool in DK weight. The hanks cooked for a couple of hours, and the Wollmeise hanks turned ochre yellow, the cotton turned pink-beige, the DK became a bright yellow, and there was no discernible effect on the linen. We kept the leaves in the nettle bath and added cotton, linen, and wool yarn, including my last remaining lace hank, and the nettle produced yellow without modifiers. Prior to adding modifiers, the yarn turned various shades of yellow, depending on what kind of fiber it was. After a couple of hours heating, we divided the nettle bath in two and dissolved the copper and iron powders separately in boiling water and added them each to the separate pots of nettle.

The iron-modified nettle dye turned my Wollmeise lace into a dark green within minutes. The cotton turned silvery gray, and the linen looked like a darker variation on its original undyed brown-gray. As for the copper, after simmering in it for two hours, the wool DK turned a mint green and my Wollmeise lace turned a shade of green that was almost identical to my rhubarb hank that underwent that dramatic chemical reaction. I’m regretting my failure to label my hanks. It’s interesting that very different plants and modifiers can produce such similar colors. I don’t have notes on how the copper modifier affected the cotton and linen.

Here’s a class photo of the yarns we dyed, minus some of the yarns that look a lot like each other. The camera and lighting overemphasized the pink and purple tones.

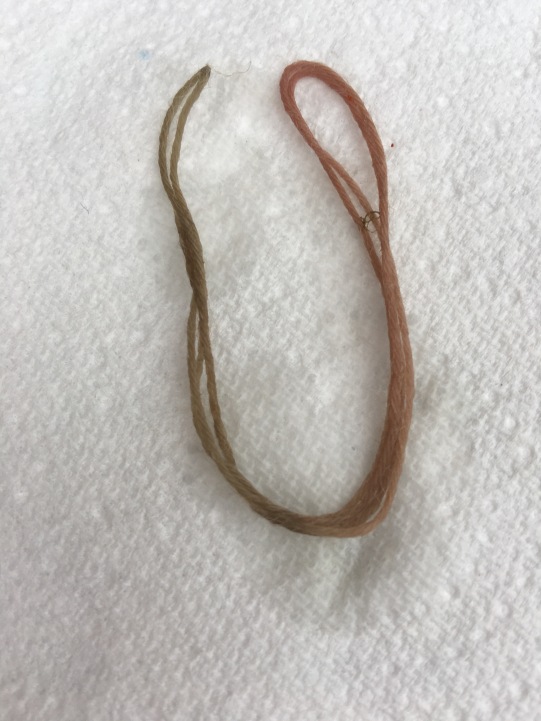

Here are some fairly accurate photos of my own Wollmeise lace hanks after they were dry.

This photo picks up more of a difference between the top and center hanks than I was able to discern in real life. I have since overdyed one of those two hanks in black bean bath, resulting in a spruce green. I just realized that these three hanks collectively spent time in every plant dye and modifier we used except for the avocado bath.

After we had finished all the dyeing, Liz and I sat down to consolidate our notes and reflect on what we had learned. Liz’s new information was about the yarn she had dyed. Color didn’t show very well against the brown of the unbleached linen she was using, and non-superwash wool felted under the heat of the dyeing process and didn’t take color as well as my Wollmeise lace yarn did. Liz also came away with the knowledge that she knows enough about this subject that she could run her own workshops, and is now starting to talk to people to set that up. My takeaway from our dyeing marathon was much more about basic methodology, as well as my personal philosophy for plant dyeing. This was the first time I had dealt with modifiers in a more systematic way than to pour lemon juice in black bean dye until the color changed or to simmer a dyed hank in my cast-iron skillet. My approach is to dye only with things that are on hand or found or abandoned, and not to use food that might be eaten. Liz kindly gave me two boxes of hibiscus tea, and I’m a little torn about what to do with them. According to my rules, I would make tea with them and then dye with the used bags… but the color in Liz’s bath was so vivid from the moment the tea bags hit the cold water! Am I going to resist such vivid colors because it violates my philosophy? On the other hand, who’s going to report me to the philosophy police?

I started dyeing with plants in order to get colors that weren’t in the Wollmeise palette, but pretty quickly curiosity became my main motivation. When I learned to look for plants that I’d never noticed before in order to extract color from them, I felt as if I was learning secrets that were hidden in plain sight. Finding plants for dyeing at specific places and times of the year connects me in a very tangible way to the here and now, and it makes me feel in some way that I can’t quantify or even articulate as if I’m living a more real and aware life because I have a deeper knowledge of what to look for. I think maybe when you really see what’s in front of you, you don’t at some late date find yourself suddenly realizing you’ve gotten old and don’t know what you did with the time. You know what you did with the time. You were paying attention.

So here’s my solution to the hibiscus tea dilemma. First I dye with one box at full potency, philosophy be damned. Then I make tea out of the other box and see what colors I can get with the used tea bags. Curiosity beats philosophy. Actually, curiosity is the philosophy.

Great blog Abby I loved reading it

LikeLike

Thanks, Monica!

LikeLike

Do you know what specific kinds of hibiscus is in the tea? There are many varieties of hibiscus, many of them hardy and native to our area. I grow some. If the flowers would be useful to you, I could collect them this summer.

LikeLike

The box doesn’t specify the botanical information of the hibiscus. Yes, yes, yes to the offer of hibiscus from your garden, with many thanks!!! Using local plants gets me where I live, so to speak. It would be interesting to compare the results with the boxed teabags.

LikeLike

Thanks for letting us see what you did. I really love that avocado stone color. I suppose plant dying is addictive…

LikeLike

It certainly is! Yes, that avocado stone dye is amazing, which isn’t bragging because Liz made it, not me. I wish I had seen what she did! I’m going to try to make a dye like hers, but there are so many variables that can produce unforeseen outcomes.

LikeLike

Another great post Abby – really interesting. I enjoyed reading it and reminiscing on our weekend.

LikeLike

Thank you, Allison! I’m so glad we’re able to get together with you and all the Sisters!

LikeLike